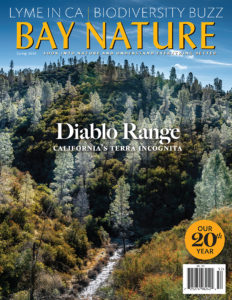

Save Mt. Diablo expands efforts to protect the 150-mile long Diablo Range

View of the Diablo Range from the top of San Benito Mountain, at 5,241 feet the Diablo Range’s highest peak. The Diablo Range covers 12 counties and 5,400 square miles, but most people have never heard of it. Copyright Stephen Joseph; used with permission.

California’s next big conservation story, right in our backyards

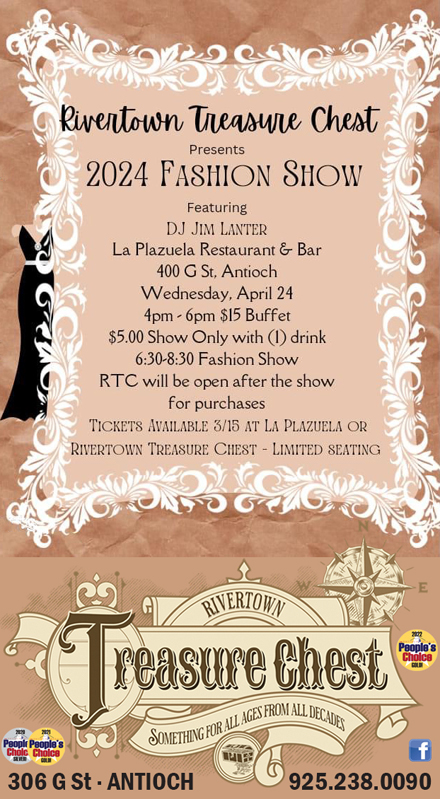

Cover of the Spring 2020 issue of Bay Nature magazine. Credit Bay Nature.

By Laura Kindsvater, Communications Intern, Save Mount Diablo

Save Mount Diablo has launched a campaign to connect Mount Diablo to the whole of the Diablo Range, a 150-mile long mountain range and biodiversity refuge that’s next door to millions of people, but that most people know nothing about.

“The Diablo Range is the missing piece of the California conservation map,” says Save Mount Diablo Land Conservation Director Seth Adams. “It’s California’s next great conservation story.”

“Seventy-five percent of the ecologically important area around Mount Diablo has been preserved,” explains Edward “Ted” Sortwell Clement, Jr., Save Mount Diablo’s Executive Director, “while in the full 150-mile range, only 24 percent of the landscape has any protection. We’re going to change that. Save Mount Diablo’s first step is defining the range as a whole for the conservation community and the public and educating them about its importance.”

Save Mount Diablo’s public educational efforts will include the full 150-mile Diablo Range. As part of this campaign, Save Mount Diablo helped to sponsor a newly published cover story and supplement about the Diablo Range in Bay Nature magazine, with the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority. “The Spine of California,” by Bay Nature Digital Editor Eric Simons, explores the most rugged, plant-rich stretch of California you’ve never heard of.

The cover story is the first article ever published specifically about the Diablo Range, and it includes the first ever published map of the public and protected lands of the Diablo Range. “Our first effort is to put this place on the map,” notes Adams.

Panoche Valley and the Panoche Hills, part of the Diablo Range. The Diablo Range is threatened by both alternative and fossil-fuel based energy development, and in the Panoche Valley, large solar farms are beginning to pop up. Credit Al Johnson.

Also, as part of the campaign, Save Mount Diablo recently expanded the geographic area in which it now does its land use advocacy; it now includes the three northern counties of 12 crossed by the Diablo Range. The organization’s primary acquisition focus remains north of Highway 580 and around the main peaks of Mount Diablo. The organization recently announced two acquisition projects on the main peaks, the 154-acre Trail Ride Association conservation easement on North Peak for which it needs to raise a little over $1,040,000 and the $650,000 Smith Canyon project adjacent to Curry Canyon.

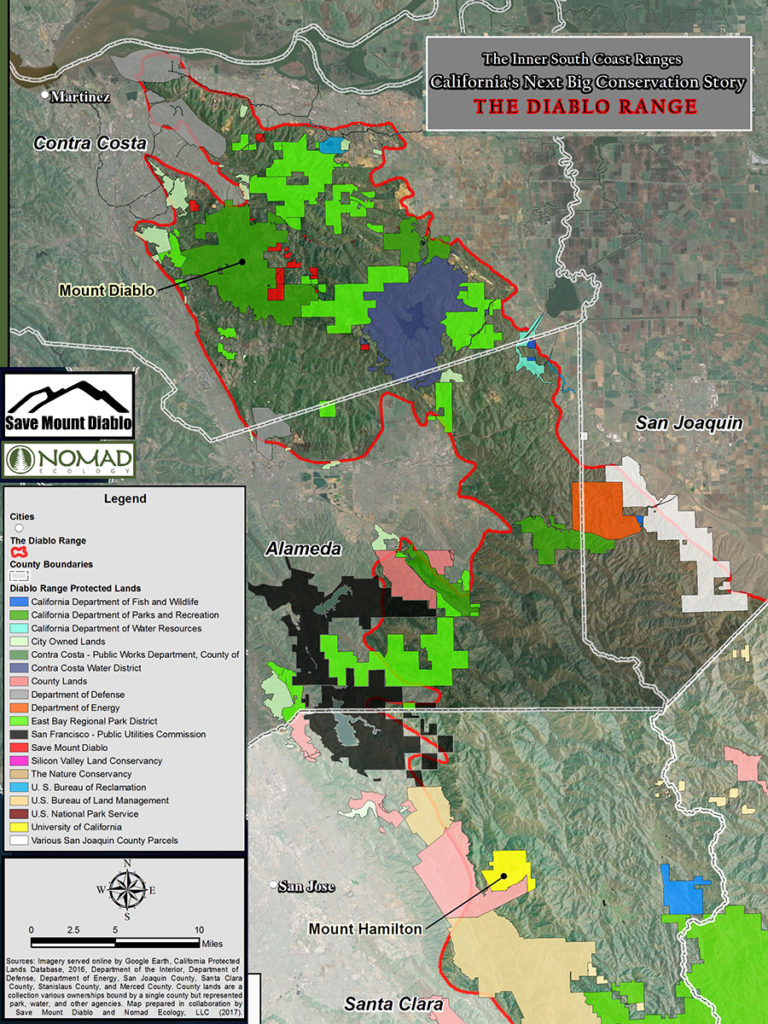

Map showing the northern Diablo Range. Save Mount Diablo recently expanded the area in which it works down to the Santa Clara County line. In addition to Contra Costa County between Highway 680 and the Byron Highway, Save Mount Diablo’s area of interest now encompasses portions of southeastern Alameda County and southwestern San Joaquin County, including a critical wildlife corridor linking Mount Diablo to the rest of the Diablo Range and a vulnerable region of spectacular biodiversity (Cedar Mountain, Corral Hollow, and the greater Mines Road area). Map prepared in collaboration by Save Mount Diablo and Nomad Ecology, LLC.

In addition to working in Contra Costa County between Highway 680 and the Byron Highway, Save Mount Diablo now also works in southeastern Alameda and southwestern San Joaquin Counties.

This area includes an essential, 10-mile-wide wildlife corridor (Altamont Pass is part of it) that connects Mount Diablo to the rest of the Diablo Range. It also includes one of the most important and vulnerable biodiversity hotspots in California.

Save Mount Diablo Executive Director Ted Clement and Land Conservation Director Seth Adams waving from on top of San Benito Mountain, at 5,241 feet the highest point in the Diablo Range. Credit Al Johnson.

According to Simons, “The 150-mile range of mountains from the Carquinez Strait to the oil fields of the southern San Joaquin Valley holds some of the largest remaining wild places in California. It is a rugged, remote, difficult realm, a biodiversity ark incised by the San Andreas Fault. It is a historic mixing place, where Central Valley Yokuts and coastal Ohlones traded and danced, where California’s ever-more-diverse future residents will seek escape and recreation. And it is nearly unparalleled in ecological significance.”

The Diablo Range stretches from the Carquinez Strait all the way to the Antelope Valley in Kern County and contains some of the largest remaining unprotected wild places in California. The mountain range is huge, rugged, and remote. Bounded by Highway 101 to the west and Interstate 5 to the east, the 150-mile long, 40- to 50-mile wide area is a blank spot on the map for the public focused on its outer grassland foothills. “Five miles in and 500 feet up,” Adams says, “oaks and chaparral appear, and it’s Mount Diablo multiplied.”

In the southern Diablo Range is a huge area of serpentine geology and associated soils. These soils are toxic to most plants, but home to many rare plant species that have evolved to handle the toxicity. Some of these plants are “serpentine endemics”—they can live nowhere else. Pictured here: the serpentine barrens at San Benito Mountain. Copyright Stephen Joseph; used with permission.

The Diablo Range covers 5,400 square miles and has many peaks, some of which are taller than Mount Diablo. The tallest one is San Benito Mountain at 5,241 feet. Mount Diablo measures at 3,849 feet.

The range is extremely important for wildlife, crossed only by two major highways at Altamont and Pacheco Passes. It serves as a reservoir of biodiversity, a core habitat for wildlife in California.

Although golden eagle populations are declining in western North America, they’re stable in California because of the Diablo Range.

Serpentine ecosystems at San Benito Mountain. Copyright Stephen Joseph; used with permission.

The northern Diablo Range supports the highest density of golden eagles on the planet. The Diablo Range could also be the source for replenishing the genetic diversity of mountain lion populations in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Tule elk, nearly hunted to extinction in the 1970s, have recovered quickly in the Diablo Range. Bay checkerspot butterflies have their last stronghold along Coyote Ridge just above San Jose. And the Diablo Range offers great habitat for California condors to expand into as they recover from the brink of extinction.

Headwaters of the San Benito River. Credit Al Johnson.

The Diablo Range is threatened by energy development (both alternative and fossil fuel-based energy), suburban sprawl, and proposed dams and reservoirs. Wind turbines endanger golden eagles and other birds. And the Panoche Valley, part of the Diablo Range, now has a 4,800-acre solar farm.

This mountain range harbors incredible biodiversity that supports many rare, endemic (plants or animals found nowhere else), or disjunct species (plants that are cut off from other populations and not expected to be there). It contains large swaths of land with serpentine soils, on which rare plant species that live nowhere else grow. And some of the soils are “vertic clays,” which also support rare and endemic plant species.

Save Mount Diablo Executive Director Ted Clement and the Diablo Range. Copyright Stephen Joseph; used with permission

Although the Diablo Range is right next to some large cities, large areas of it have limited to no cell phone coverage, light pollution, or major roads, an indication of its habitat connectivity.

Read more about the Diablo Range and Save Mount Diablo’s work to protect it in the Bay Nature cover story.

The Panoche Hills, part of the Diablo Range. Credit Al Johnson.

About Save Mount Diablo

Save Mount Diablo is a nationally accredited, nonprofit land trust founded in 1971 with a mission to preserve Mount Diablo’s peaks, surrounding foothills, and watersheds through land acquisition and preservation strategies designed to protect the mountain’s natural beauty, biological diversity, and historic and agricultural heritage; enhance our area’s quality of life; and provide recreational opportunities consistent with the protection of natural resources. Learn more at www.savemountdiablo.org.

the attachments to this post:

10 – #8711 Ted Clement Diablo Range (Stephen Joseph)

9 – Headwaters of the San Benito River (Al Johnson) small

8 – San Benito Mtn #8716 (Stephen Joseph)

4 – Ted Clement and Seth Adams atop San Benito Mtn cropped (Al Johnson)

3 – Diablo_Range Conserved Lands_North – East Bay & San Joaquin

5 – Panoche Valley and Panoche Hills (Al Johnson) small